EAST BAY TIMES: ROADWORK GETS TECHIE: DRONES, ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE CREEP INTO THE ROAD CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY

High above the Balfour interchange on State Route 4 in Brentwood, a drone buzzes, its sensors keeping a close watch on the volumes of earth being moved to make way for a new highway bypass. In Pittsburg, a camera perched on the dash of a car driving through city streets periodically snaps pictures of potholes and cracks in the pavement. In the same city, another camera monitors pedestrians, cyclists and cars at the corner of Harbor and School streets, where 13-year-old Jordyn Molton lost her life late last year after a truck struck her.

Although the types of technology and their goals differ, all three first-of-their-kind projects in Contra Costa County aim to offer improvements to the road construction and maintenance industry, which has lagged significantly behind other sectors when it comes to adopting new technology. Lack of investment stifled innovation, said John Bly, the vice president of the Northern California Engineering Contractors Association.

However, with the recent passage of SB 1, a gas tax and transportation infrastructure funding bill, that’s all set to change, he said.

“You may see some of these high-tech firms find new market niches because now you have billions of dollars going into transportation infrastructure and upgrades,” he said. “That’s coming real quick.”

It’s still so new that Bly was hard-pressed to think of other areas where drone and artificial intelligence software is being integrated into road construction work in the state. The pilot programs in the East Bay “are cutting edge,” he said.

At the Contra Costa Transportation Authority, Executive Director Randy Iwasaki has been pushing to experiment with emerging technology in the road construction and maintenance industry for several years, so when the authority’s construction manager, Ivan Ramirez, came to him with an idea to use drones in its $74 million interchange project, Iwasaki was eager to try it.

“We often complain we don’t have enough money for transportation,” Iwasaki said, adding that the use of drones at the interchange project in Brentwood would enable the authority’s contractors to “save paper, save time and save money.” Traditionally, survey crews standing on the edge of the freeway would take measurements of the dirt each time it’s moved. The process is time consuming and hazardous, Ramirez said.

That’s only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to potential applications for the drone’s technology, which could also be used to perform inspections on poles or bridges and perform tasks people haven’t yet thought of.

“As you begin to talk to people, then other ideas begin to emerge about where we might be going, and it’s propelling more ideas for the future,” Ramirez said. “By not having surveyors on the road, or not having to send an inspector up in a manlift way up high or into a confined space, not only is it more efficient, but it will provide safety improvements, as well.”

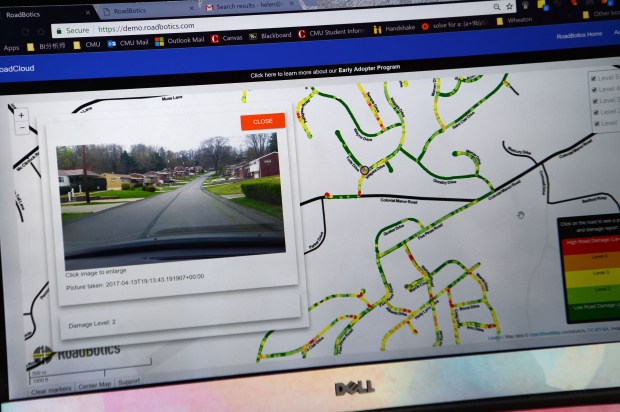

Meanwhile, in Pittsburg, the city is working with RoadBotics on a pilot program to better manage its local roads. The company uses car-mounted cellphone cameras to snap photos of street conditions before running that data through artificial intelligence software to create color-coded maps showing which roads are in good shape, which need monitoring and which are in need of immediate repairs.

The company’s goal is to make it easier for city officials to monitor and manage their roads, so small repairs don’t turn into complete overhauls, said Mark DeSantis, the company’s CEO. Representatives from Pittsburg did not respond to requests for comment.

“The challenge of managing roads is not so much filling the little cracks — that’s not … much of a burden,” DeSantis said. “The real challenge is when you have to repave the road completely. So, the idea is to see the features on the road and see which ones are predictive of roads that are about to fail.”

At the same time, Charles Chung of Brisk Synergies is hoping to use cameras and artificial intelligence software in a different way — seeing how the design of the road influences how drivers behave. At the corner of Harbor and School streets, the company installed a camera to watch how cars, cyclists and pedestrians move through the intersection and to identify why drivers might be speeding. In particular, the company is also trying to determine how effective crossing guards are at slowing down cars, he said.

Brisk Synergies is still in the process of gathering data on that intersection and writing its report, but Chung said it was able to use the software in Toronto to document a 30 percent reduction in vehicle crashes after the city made changes to an intersection there. Before, documenting the need for changes would require special crews to either monitor the roads directly or watch footage from a video feed, both of which take time and personnel.

While only emerging in a handful of projects locally, these types of technology will become far more prevalent soon, said Bart Ney of Alta Vista Solutions, the construction-management firm using drones on the SR 4 project.

“We’re at the beginning of the wave,” he said. “Like any disruptive technology, there is a period when you have to embrace it and take it into the field and test it so it can achieve what it’s capable of. We’re on the brink of that happening.”